Sears Canada Tarnishes the Gold Standard of Pensions

/

*****

Michael J. Armstrong, Brock UniversityLike many department stores, Sears Canada has struggled with competition from specialty stores and online retailers. Its bankruptcy will eliminate some 12,000 jobs and leave 16,000 retirees worried about their pensions.

It’s just the latest signal that employees and regulators should rethink their approaches to defined-benefit pensions.

Pensions are promises

Pensions represent deferred wages, money promised to employees in the future. With defined-contribution plans, employers make short-term promises to invest each year in their pension accounts. The eventual pension cheques depend on how the investments perform.

With defined-benefit plans, employers also promise to invest more if investment returns are poor. That reassurance makes those plans the “gold standard.”

However, such top-ups may be needed decades after the promises were made. If you start work at 25 and retire at 65, your first pension cheque arrives 40 years after your first paycheque. That very long-term promise presents two risks for employees.

Funding shortfalls

First, the money might not be there when needed. Defined-benefit plans should pay better than defined-contribution plans during recessions. But that’s when employers are least able to invest.

For the private sector, 40 years is roughly six economic cycles of boom and bust. Will your employer survive that?

Consider Sears. Its retirement funds are short $308 million, forcing a 19 per cent pension cut. That may be partly replaced if liquidation sales go well.

(Incidentally, consulting firm Morneau Shepell now administers the impoverished plan. That indirectly connects federal Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s name to another pension controversy.)

Or look at ex-telecom Nortel. Its 2009 bankruptcy cut pensions 30 per cent. Twenty thousand pensioners waited eight years to see how much might be restored. That’s not very “defined.”

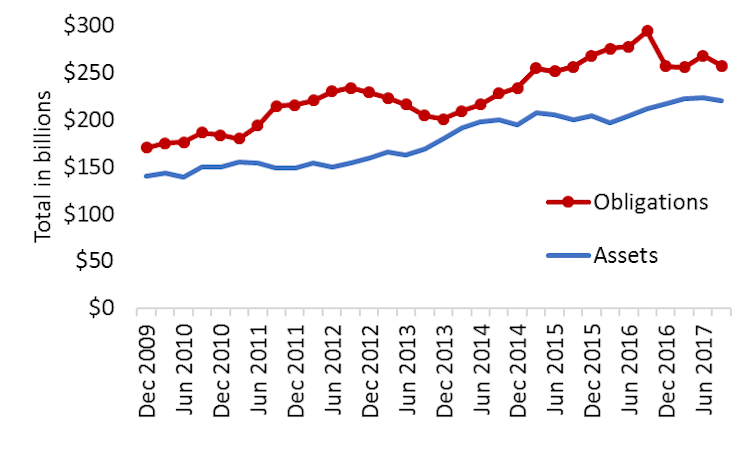

Unfortunately, pension underfunding is common. In Ontario, single-employer defined-benefit plans are short $37 billion in total. Only 18 per cent are fully funded. Those numbers exclude plans serving multiple employers, like the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System.

Public sector plans face other risks. Forty years is about 10 election cycles. Will all those politicians keep their predecessors’ promises?

They didn’t in Detroit. To escape bankruptcy in 2014, the city cut pensions by 4.5 per cent. Some cuts were retroactive – retirees had to give money back.

And they didn’t in Rhode Island. In 2011, that state had only 56 per cent of the pension money needed. To avoid disaster, it reduced retirees “defined” benefits.

Transient employees

The second risk with defined-benefit pensions is employee turnover. Plans typically calculate payments based on age and years of service. If you work there longer, you’ll receive more.

But quitting sooner gets you less. Depending on where you work and how long, you may get only your contributions back, plus interest. In effect, the defined-benefit plan becomes a defined-contribution one.

Or you’ll receive a deferred pension based on your salary when you quit, say at age 35. That’s likely much lower than your final salary 30 years later at age 65. So, it’s “defined” smaller.

Defined-benefit pensions are nicknamed “golden handcuffs.” They penalize people who switch employers.

But people do switch. Professionals change companies for career advancement. Temporary workers struggle from contract to contract.

Half of U.S. workers have been with their current employer less than 4.2 years. For those aged 55 to 64, 14 per cent have been there less than two years. That jumps to 38 per cent for those 25 to 34. For them, defined benefits are no better than defined contributions.

I’m not suggesting employees should abandon defined-benefit plans. They’re great if employers and employees are stable. But they aren’t risk-free, so some unions might consider bargaining for other benefits instead.

Government action needed

Meanwhile, governments should increase pension protections. For example, Ontario’s Pension Benefits Guarantee Fund will soon protect up to $1,500 of monthly pension payments. Other provinces should follow suit.

Unfortunately, Ontario is also letting pension funds become 15 per cent underfunded before requiring employer top-ups. Currently, 58 per cent of plans fit that category. That allows employers to ignore temporary investment downturns. But it also risks greater shortfalls during bankruptcies.

Sears pensions are 19 per cent underfunded, despite the company making top-ups. Imagine a future company bankruptcy with 19 per cent underfunding below the 15 per cent allowance. Retirees would lose 34 per cent of their pensions.

The federal government should also act. It could ban dividend payments whenever pensions are underfunded. Some corporate loan agreements already contain similar restrictions. That could have helped Sears workers.

Bankruptcy laws need updating too. Current rules first pay off secured debts, like mortgages. Underfunded pensions are considered unsecured debts. They get paid last with whatever money is left.

A Bloc Québécois proposal would put pensions before secured debts. As an employee, I find that tempting. But as a business professor, I think it’s extreme. Instead, I prefer the NDP proposal to make pensions equal to secured debts. That would improve pensioners’ prospects while respecting mortgagees’ rights.

![]() The Liberals advocated for similar changes while in opposition, and federal Innovation Minister Navdeep Bains says he’s open to discussions now. Is he open to action?

The Liberals advocated for similar changes while in opposition, and federal Innovation Minister Navdeep Bains says he’s open to discussions now. Is he open to action?

Michael J. Armstrong, Associate professor of operations research, Brock University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-3[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476525034-QRWBY8JUPUYFUKJD2X9Z/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-3%5B2%5D.jpg)

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-2[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476491497-W6OZKVGCJATXESC9EZ0O/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-2%5B2%5D.jpg)

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-4[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476508900-TJG5SNQ294YNOCK6X8OW/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-4%5B2%5D.jpg)