Cracking Down on Retail COVID-19 Profiteers in Canada

/stock image

By Sylvain Charlebois

Even if they’ve never really had a good reason to, many Canadians have felt food insecure lately. Access to food was a concern for a while. Affordability is certainly a close second. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, every now and then, consumers have taken to social media to report inflated prices on the part of some retailers. Even though the accusations were warranted in some cases, the evidence in other cases was weak at best. While artificially inflated food prices at retail may be possible in Canada at any time, the practice is highly unusual.

For one thing, the risks are too high for everyone involved. Social media makes it so easy to call out suspicious practices, whether or not the accusations are valid. And we have seen cases like this already during the COVID-19 crisis. But consumers appreciate knowing that someone has their back. The Ford government last week in Ontario introduced fines for price gouging, the first provincial government to do so since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Corporations involved in gouging could face fines as high as $10 million. Company leaders could also face fines as high as $500,000 and a year in jail.

These are severe sanctions. But price gouging is difficult to prove, especially when it comes to food. Food inflation is a natural economic phenomenon. Many factors which the food industry has little control over will influence retail prices, including the currency, energy costs, labour costs with higher minimum wages – the list is endless. Most grocers make a razor-thin profit of anywhere between 1% to 2%, on billions in sales at retail. The margin of error is equally thin. If the Canadian dollar drops suddenly, prices need to be adjusted quickly. That’s what led to the cauliflower incident a few years ago.

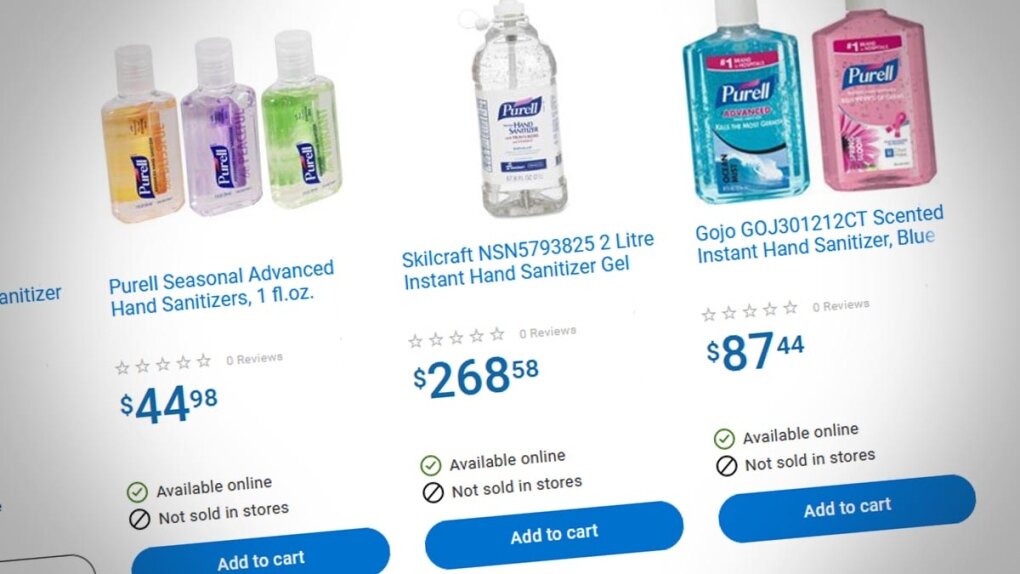

price gouging on walmart marketplace. photo: ctv news vancouver

The only way to build a case in price gouging or price fixing at retail is by accommodating whistle-blowers. That’s exactly what happened with the bread price fixing scandal, which had been going on for 14 years. But the investigation required two companies, Weston Bakeries and Loblaws, to out themselves to the Bureau in order to launch a two-year undercover investigation on five other companies. For their cooperation, both Loblaws and Weston Bakeries received immunity. The investigation, according to some reports, cost nearly $500,000, and is still ongoing after 5 years. Safe to say that these cases are difficult to prove. But historical data is key during such investigations, the access to which is critical to build a case. Going to social media will only make things more difficult for anyone looking into the matter.

The audience for the Ford Government’s new regulations against price gouging was clearly consumers themselves, not the industry. In an era of self-isolation coupled with a sentiment of communal suspicion, it was the right thing to do, regardless if exaggerated food price inflation was happening or not.

Food price monitoring since the beginning of the crisis suggests price fixing practices are almost certainly non-existent. Although meat prices, especially pork and beef, are unusually higher than expected. Farmgate prices are much lower while retail prices are reaching new heights. Even though some categories have seen increases, food prices have behaved normally, for the most part. We are expecting the food inflation rate to be at 4% this year, so prices should go up, regardless. Meat prices could go up by as much as 6% this year, so consumers should be noticing increases by now. Nothing suggests prices are increasing due to abusive pricing since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. In the dairy and bakery categories, prices were already increasing before COVID-19 started changing our lives.

one grocery store profiteering on demand for lysol wipes. photo: ctv winnipeg

During times when everyone is watching everyone else, it’s quite common – too common, in fact – to report any sort of irresponsible behaviour or breaches to our public health regulations. For a grocer or any retailer to unjustifiably increase prices only to have its reputation damaged overnight would be unwise, which is why all of them are being extremely careful. Exceptions do exist though, so consumers should be careful with the power social media gives them.

Instead of accusing retailers on social media, the Competition Bureau is the best place to go for protection. They need the evidence and the public’s cooperation. Since the beginning of the crisis, we have seen false information galore. We need to be vigilant as to which information is accurate.

One thing COVID-19 has changed is our access to discounts. Weekly flyers are getting progressively thinner, and discounted food products are fewer and farther between. Grocers are clearly focused on other issues right now, which is why we should expect fewer items to be on sale in stores. Online, it’s even worse. In fact, online shopping was never a place where bargains were easy to find. Grocers cover margins by keeping prices higher so consumers end up paying for delivery, and the labour required to put together their order.

After all, convenience and safety are premiums grocers can charge for, and that’s not criminal. It’s just business.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is Dean of the Faculty of Management at Dalhousie University in Halifax. Also at Dalhousie, he is Professor in food distribution and policy in the Faculty of Agriculture. His current research interest lies in the broad area of food distribution, security and safety, and has published four books and many peer-reviewed journal articles in several publications. His research has been featured in a number of newspapers, including The Economist, the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, Foreign Affairs, the Globe & Mail, the National Post and the Toronto Star. Follow him on twitter @scharleb.

TODAY’S TOP HEADLINES

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-3[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476525034-QRWBY8JUPUYFUKJD2X9Z/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-3%5B2%5D.jpg)

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-2[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476491497-W6OZKVGCJATXESC9EZ0O/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-2%5B2%5D.jpg)

![Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-4[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/529fc0c0e4b088b079c3fb6d/1593476508900-TJG5SNQ294YNOCK6X8OW/Retail-insider-NRIG-banner-300-x-300-V01-4%5B2%5D.jpg)

Sylvain Charlebois says that a code of practice is required to save the industry, and if nothing is done the consumer will also suffer.